One of the “too many futures” that Stanislaus believed available to his brother was that of a tenor (I). While Joyce’s singing career did not extend beyond sharing a stage with John McCormack in the Antient Concert Rooms in August 1904 (JJII 168), music was to exert a continual influence on his life and art, whether in his friendships with composers such as George Antheil and Otto Luening or in the title of his first published book Chamber Music. Joyce even likened the writing of Ulysses to musical composition (JJII 436)—most notably in the case of “Sirens” and the fuga per canonem. In this paper I riff on that theme, focusing in particular on the music hall and how Joyce used its conventions and clichés, starlets and catch cries in the writing of Ulysses.

A great deal of critical work has been done on Joyce and music, of course, and in the oft-related sphere of his connexion with popular culture. Austin Briggs, for one, has written on “The Brothel as Theatre” in “Circe”; Zack Bowen and David Hayman have explored the influence of the Dublin Christmas panto on the selfsame episode. More generally, Don Gifford’s annotations range over the entire eighteen episodes Ulysses, identifying numerous allusions and nods to the halls. And Cheryl Herr also deals with turn-of-the-century music hall in her Joyce’s Anatomy of Culture. But whereas Herr sees the references in “Circe” as Joyce’s commentary on 1904 class relations, in this paper, I focus on how the music hall functions as a structuring device in the composition of the chapter. Not unlike the Homeric scaffold that Ezra Pound deplored, Joyce used music hall conventions and celebrities as stopgaps and transitional devices in the drafting of his fifteenth episode.

I do not claim that the music hall is the only lens through which to view the composition of “Circe.” Quite apart from the Homeric correspondences and within the realm of theatre alone, precursors and sources for the episode include Thomas Otway’s The Souldier’s Fortune; Fluabert’s La Tentation de Saint Antoine; the early versions of Yeats’ The Countess Cathleen that included the lyric “Who Goes with Fergus?”; and Apollinaire’s Les Mamelles de Tirésias. And even as far as music hall is concerned, there are potential links that must finally be dismissed as mirrors and blue smoke. Does Bloom’s trial owe anything to the legal scraps of the principal girl of this article, Katie Lawrence (1870-1913)? Unlikely. What of the Judge and Jury shows of the 1840s and 1850sthemselves a precursor of the music hallduring which the “learned Judge” Renton Nicholson of the Coal Hole (U 15.1255?) heard cases before an audience of drinkers acting the part of jury? Professional actors staged topical murders (cf. Henry Flower) or breaches of promise (Martha Clifford) with one of the company even playing The Prostitute, “with dialogue and stage business to match” (Watters 34-35), but in relation to “Circe” the sham trials remain a tantalizing intertext only.

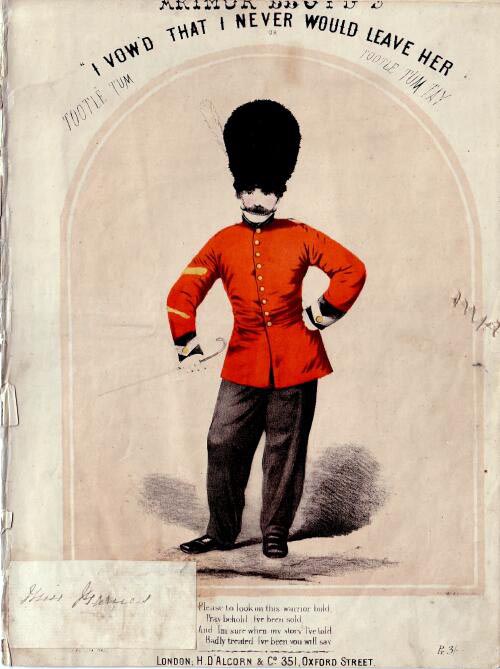

Many aspects of the episode connote the halls, from Bloom’s Fregolian quick-change to the Italianate Maginni instructing the dance corps (II). One can see in Zoe’s unrelenting stream of commonplaces and trite phrases something of the vaudeville chirpiness of knockabout comedy. Even Florry’s misunderstanding of Stephen (“They say the last day is coming this summer” U 15.2129) owes something to the same crosstalk that informs the end of “Anna Livia Plurabelle”: “Are you not gone ahome? What Thom Malone?” (FW 215.32-33). Few characters in “Circe” escape the music hall net; indeed, Joan Jastrebski has traced their very reappearance in the episode to the halls’ trope of up-to-the-minute topicality (172). Corny Kelleher, for instance, with his tooraloom refrain adapted from Arthur Lloyd’s “I Vowed that I Never Would Leave Her”(1), mockingly claims kinship with Bloom as a fellow “old stager”—a phrase that is commonly, if erroneously, explained by way of the theatrical stage (OED). This sense is strengthened by Kelleher’s earlier “No, by God, says I, my dancing days are done”—subsequently revised to “No, by God, says I” (III: now U 15.4868-69). The episode also references the theatre mechanics of limelight and its initial Potemkin setting (those grimy turned flimsy houses of the opening) stands in for stage scenery.

In the Tyrone Street brothel, Stephen, Bloom and Lynch consort with the madam Bella Cohen and three prostitutes. From the various published editions we know these as Zoe Higgins, Kitty Ricketts and Florry Talbot. Ellmann claims that the latter two were “probably modelled on contemporary prostitutes. Florry Talbot, for instance, was probably Fleury Crawford. […] Kitty Ricketts suggests Becky Cooper” (JJII 368). Becky Cooper lived in the former Tyrone Street until the late fifties and when one hears of her today it is usually because she crops up in the second verse of the Dublin folksong “Dicey Reilly” (IV). I will shortly outline an alternative antecedent for Kitty—one with its own musical associations.

The characters’ names weren’t always so. In the draft of “Circe” now in the Poetry Collection of the University at Buffalo, “Florry” is spelt uniformly as “Florrie” and Kitty Ricketts appears as Kitty or Kate Lawrence. Joyce describes the scene in the brothel as follows:

On a rug of matted sheepskin before the fireplace Lynch is seated crosslegged, his cap […] back to the front. Kitty Lawrence, a bony whore in street costume, sits on the side of a high sofa, swinging her leg (Herring 223).

The next three occurrences of the character in the draft are on the next page, in speeches assigned to “Kate” before the full name “Kate Lawrence” appears twice in stage directions on pp. 13r-14r, when Zoe

takes a piece [of chocolate] and nibbles. Kate Lawrence does the same.

[…] Kate Lawrence offers a piece to Bloom (Herring 229).

Though the girl had been called “dear Kitty” since the fair copy of “Oxen” (V: now U 14.787) Joyce apparently saw no problem in changing her name to “Kate” in “Circe”understandably so when one considers that “kitty,” slang for a prostitute or a loose woman, is not necessarily the character’s name. And, anyway, as will be explored, the name “Kate” may have always been planned as only a temporary measure. Revising the draft, in any event, Joyce crossed out both the occurrences of the surname “Lawrence,” replacing them with “Ricketts.” Phillip Herring, commenting on the Buffalo copybook in the foreword to his 1977 transcript of the document, speculated that Joyce made these substitutions after “perhaps having had second thoughts about baiting a rival novelist whom he did not admire” (199). Joyce does not have D. H. Lawrence in mind at all herein fact Kate Lawrence, or more usually Katie Lawrence, was the name of a music hall and variety performer who rose to prominence in the 1890s. This sheet-music cover(2) shows her in 1890, aged nineteen or twenty.

Now if one accepts that the draft name Kate Lawrence refers outside of Joyce’s text in progress, a trawl of newspapers from the end of the nineteenth century is bound to turn up other candidatesboth fictional and historical. There is a character called “Kate Lawrence” in an 1850s sketch called The Rifle Volunteers, for instance; the bride of one Rev. John Stewart, who was married in April 1882, was also so named. The papers mention an illegitimate three-year-old infant who died in 1883 owing to her mother’s negligence; a candidate who passed a religious exam; a pupil who won a £10 bursary; and a madwoman on a bus (VI). No doubt, connexions could be forged for each of these Kate Lawrences to Ulysses, but I argue that Joyce had the artiste in mind. As to the slight discrepancy between Kate and Katie, while the latter is the more usual choice, either name appears in advertisements and puff paragraphs of the period. And occasionally both turn up in a single context. The Erathe leading trade weekly of the dayfor Saturday, 28 March 1885, for example, advertised on page 24:

The Gipsy Maid.

M I S S K A T I E L A W R E N C E,

great success at the

Palace of Varieties, Gloucester.

The Citizen, March 24th:–

Miss Kate Lawrence, who deservedly carried off the honours of the

evening, possesses an attractive appearance and a taking style of

singing. Her songs were “Johnny, my darling,” “Stella, the Zin-

gara,” and a pretty American song and dance “Where the pretty

roses bloom.” The last item was loudly encored, and in response Miss

Lawrence executed a little “stepping.” The dresses worn by Miss

Lawrence were exceedingly pretty, and are deservedly worthy of

special mention.

Monday next, GAIETY, LEICESTER.

Agent, G. WARE.

Lawrence existed for her fin-de-siècle audience, just as her fellow artistes did, in a heavily mediated space encompassing such trade magazines and sheet-music covers and which ranged across everything from performance posters, playbills, promotional postcards, novelty bookmarks and cigarette cards(3) to souvenir ceramic figurines(4) and biscuit tins. In “Wandering Rocks” when young Master Patrick Dignam looks at a performance poster and identifies the artiste featured as “One of them mots that do be in the packets of fags Stoer smokes,” he figures the artiste in terms that are entirely mediatory (U 10.1142–44). By inscribing Lawrence’s name into the text of “Circe,” however temporarily, Joyce co-opts the popular-culture textuality in which she and her fellow stars were situated to his own aesthetic ends. If we return to Lawrence’s first appearance in the draft, for example“Kitty Lawrence, a bony whore in street costume”this reproduces, in a parodic fashion, the manner in which an artiste like her would have been billed in the entertainment magazines. An advertisement in The Entr’acte from the start of her career reads:

B O N N Y K A T I E L A W R E N C E

(Pupil of J. W. Cherry),

DASHING SERIO AND DANCE ARTIST.

All new songs.

PEOPLE’S PALACE, PECKHAM … (3rd week)

Other Engagements pending.

AgentGEORGE WARE (VII).

Lawrence was born in 1870 and by her early teens had begun to make a name for herself on the music hall stage; she was thirteen at the most when the above notice appearedbonny indeed. Several years later and almost a decade before he was to make Joyce’s acquaintance, Arthur Symons, who wrote on the halls for The Star,declared in a letter to the newspaper’s editor that Katie Lawrence was“the incarnation of the most perfectly artistic vulgaritya true artist, a child of nature. […] She dances with an abandonment that one rarely sees on the English stage” (VIII). And during the period of her greatest success, George Bernard Shaw, as music critic of The World, complimented her “fine ear for pitch and […] power of making a well-marked refrain go with a perfect swing” (IX).

Katie Lawrence performed numerous times in Ireland, coming over from England as early as February 1885. Her touring circuit generally took her to Dan Lowrey’s Music Hall in Dame Street (itself mentioned in Ulysses) and, following a run there, to the Belfast Alhambra (X). The report of The Era on a September 1885 performance at Dan Lowrey’s gives a flavour of the contemporary entertainment:

The negro comics, Messrs Brown, Newland, and Wallace create roars of laughter in their humorous sketch Black Justice. The “sketchists” and boxers, Messrs Kelly, Murphy, and M‘Mahon have proved a great success, and the child actress Lilly London is much appreciated. Miss Kate Lawrence and Miss Flora Devine earn warm applause; Mr W. M‘Mahon a clever mimical comedian, is also doing well (XI).

A young, middle-class Dubliner like Joyce may well have been aware of Lawrence to judge from the frequency with which she played at Dan Lowrey’s in the 1890sshe appeared at least once a yearand, from 1903, at the Tivoli. The month before he left Ireland with Nora Barnacle, “Dublin’s Greatest Favourite Comedienne” was engaged to perform twice nightly “at great cost” (XII). That is not to imply that Joyce ever actually saw her take to the stage, however. He could have known of Lawrence from the posters and promotional literature that littered Dublin, as other major cities of the British Empire.

On the hoardings, the fight for an artiste was to top the billnot to be listed down among the wines and spiritsand Lawrence’s rising star can be charted from the billing she gets in contemporary advertisements. In the early days of her career, she was last among the artistes listed in an advertisement for “The Royal (late Weston’s) Holborn” in London. When she appeared at the Canterbury in August 1886 she was similarly ranked pretty far down the bill(5). Despite this, she had evidently made enough of a name for herself that Miss Florrie Deveen could appear earlier the same year billed as “sister to Kate Lawrence”one might imagine a link here to Kitty’s sister-whore Florrie/Florry. Three years later, at the same London venue, Katie was placed considerably higher on the promotional poster(6). And by December 1893, she topped the bill(7) at Gatti’s Charing Cross music hall (though “Tom White & his Arabs” headlined). In March of that year she completed a “very successful engagement at Gatti’s (Charing-cross) of thirteen weeks.” Across the water in Ireland, she was achieving equally prominent notice around this time: in August 1892 The Belfast News-Letter announced, “Positively last six nights of Miss Kate Lawrence” at the Alhambra. According to The Era,the hall “was crowded each night to hear Miss Kate Lawrence, who is appearing again this week with success” (XIII). A few years later, such was her reputation that a programme for November 13, 1899 advertised “Monday next—Miss Katie Lawrence.”

For all artistes, the attainment and prolonging of success meant travel—whether to the provincial theatres of England, or to Dublin or Belfast—or even further afield. Katie Lawrence left the British Isles to tour Australia in January 1888 and was away until May ’89; in the early 1890s she was in the U. S.; and a few years later she took a tour of South Africa (XIV). It was while she was in New York in 1892, however, that the wheels that garnered Lawrence her greatest success were set in motion. She met the Englishman Harry Dacre, who was unsuccessfully touting a song he had written. She heard it, promptly bought it and introduced the song to English audiences on her return in early 1893.

This was the manner in which all music hall artistes operated: they did not simply sing songs wily-nily but established a familiar repertoire for themselves by buying up rights and, as they became more successful, putting their portraits on the published versions of songs. The market for sheet music as a commodity ranged from the expensive four shilling printing, complete with lithographed cover, to the sixpenny popular edition—at a time when the average weekly wage for an adult male industrial worker in England was 21/- (XV) the high-end output remained the preserve of the middle-class parlour. In this way sheet music generally publicised the singer of a song as much as its composer and considerable pains were taken to protect the rights of both the singer and publisher (piracy being rife during the period: XVI). Lawrence herself was involved in a number of legal disputes—as both plaintiff and defendant.

The Dacre song that launched Katie Lawrence was the immortal “Daisy Bell”(8) or “A Bicycle Made for Two” with its chorus line of “give me your answer do.” It propelled Lawrence, then in her early twenties, to music-hall superstardom. Such was its appeal to audiences that she was known by the name “Daisy Bell”—even though by the 1890s “Miss Katie Lawrence” was as much a stage name as “Daisy Bell” for the artiste, now Mrs. George Fuller—and advertisements and puff paragraphs frequently alluded to the song as her signature piece. The Belfast News–Letter for Monday September 4, 1893 related, “Miss Kate Lawrence, the brilliant vocalist, is to reappear in some of her popular songs, ‘Daisy Bell’ and ‘Oh, My Bonnet.’” Advertisements in The Irish Times even described her as the singer of the “original ‘Daisy Bell’” (XVII), since by the late 1890s the popularity of the song was such that it had spawned numerous sequels, parodies and imitations. As early as the year of Lawrence’s initial success, Horace Lennard and Herbert Simpson came out with “A Bicycle Will Not Do: Daisy Bell’s Answer” (sung by Miss Jenny Valmore); Dacre’s himself penned the 1894 sequel “Fare You Well, Daisy Bell”(9); Harry Anderson wrote a parody called “Four Wheeler Made for Six”; and a second “Farewell, Daisy Bell”(10) was released in 1905. Rip-off was standard practise for the music halls with Lawrence herself singing “The Ta–ra–ra Lament” at the time of Lottie Collins’ triumph with “Ta–ra–ra–boom–de–ay.”(11)

Like its fellows, the Harrington and LeBrunn song “Salute My Bicycle”(12), which Marie Lloyd—of “And your other eye” fame (U 11.148)—had success with in 1895, capitalised as much on the emergence of the bicycle as a means of workaday conveyance as on Dacre’s and Lawrence’s hit. One John Kemp Starley developed the safety bicycle in England in 1885 (its basic design of two identically sized wheels with a rear chain-drive is that still in use today) and its widespread adoption in the later years of the decade, particular by women, lead to a redefinition of Victorian gender roles—impacting on all aspects of society from the “advanced costume” of ladies’ cycling apparel to billboard advertisements (Wosk 97).

Both the subsequent enthusiasm for cycling and reactionary unease found their outlet in the music halls, whether in the lyrics of topical songs or in the antics of acrobat performers(13). The concern over/celebration of the bicycle as an “instrument of the ‘new freedom’” and its attendant “New Woman rampant” rider were immortalised, as Holbrook Jackson recalled, in Dacre’s “Daisy Bell” (204). Not to mention the numerous other songs of the period. In Ulysses, both Bloom and Molly think of the apparently recent Dublin phenomenon of lady cyclists—in Molly’s words: “those brazenfaced things on the bicycles with their skirts blowing up to their navels” (U 18.290–91)—but safety bicycles had been established as a commodity fetish long before June 1904. On the programme of the Empire Palace Theatre for February 21, 1898 (as Lowrey’s was then called) advertisements for no less than four rival bicycle makers feature—including the suggestive Aeolus Cycles of 26 Bachelor’s Walk.

Lawrence created a sensation when she appeared on stage wearing the boy’s Norfolk suit of the sheet-music cover and singing “Daisy Bell”but, in fact, male impersonators were a commonplace of the Victorian music hall. While she was never explicitly billed as a male impersonator as such (what with a repertoire that included such songs as the 1895 “Daddy’s Gone to London” and 1900 “Thinking of the Lad Who Went Away”), nevertheless, in “Daisy Bell” Lawrence sang as the male lover

We will go tandem as man and wife Daisy Daisy

Ped’ling away down the road of life I and my Daisy Bell

—a role continued in her 1899 “The Ship that Belongs to a Lady” and 1901 “Oh! Jack, You Are a Handy Man.” Among “Circe’s” debts to the music hall is its use of this stage transvestism. Early in the episode Bloom meets—or imagines he meets—his old flame Josie Breen. She is dressed in “man’s frieze overcoat” and, at one point, reminiscences with Bloom, saying, “You were the lion of the night with your seriocomic recitation” (U 15.386, 447-48). Both of these terms are drawn from the music hall. The lion(14) or lion comique, a term coined by J. J. Poole of the South London Hall (Watters 56), denoted a swaggering male stock character, one who combined a repertoire of riproaringly hedonistic songs with audience banter. The serio-comic, on the other hand, was a female role: Lawrence herself was often billed as such (XVIII). Not only do Mrs. Breen’s words splice the halls personae of swell and ingénue, but her very attire sets her up as a version of the male impersonator(15)—a stage character whose origins have been traced to the music hall itself as he/she parodies the lion comique role (Kift 50-51).

“Circe’s” moment of explicit gender bending also draws on the music hall. Bloom’s transformation, at the height of the episode, into a pig is clearly a nod to the Homeric Circe. But Joyce goes further: he has Bloom and Bella both transform sexually, with Bella becoming Bello and Bloom the ingénue Ruby. While this literalizes the theatricality of the music hall stage, Joyce’s composition method for this section of “Circe” also stems from music hall conventions. This poster(16) for a Christmas pantomime advertises a “Grand Transformation Scene” as part of the proceedings. The transformation scene, a panto standard, functioned as a distinct theatrical entity but, at the same time, was also a transitional device in that it provided a visual interlude during the major scene change between the panto’s two constituent parts of fairy tale and harlequinade.

The transformation scene figures, both literally and compositionally, in “Circe.” The Buffalo copybook where Kate Lawrence first makes her appearance comprises two discrete blocks of text, separated by eight blank pages (Spielberg 47). At the end of the second block—which is itself composed of fragmentary scenes—and towards the end of the entire copybook, Joyce inscribed a schema for the next draft of the episode:

Schema

rMoney talk

rFortune telling

SD. flies

bDance of hours

bSD’s mother

Transformation scene (Herring 247)

The superscripts here denote colours of crayon cancellation—(r)ed and (b)lue—and the cancelled pairs represent couplings of discrete scenes. These pairings are present in the next draft of this section of the episode—the so-called “Quinn draft,” which is now at the National Library of Ireland—and the last line of the schema is central to the particular disposition of the document.

Unlike the Buffalo copybook, the Quinn draft is written on large loose sheets. It comprises two distinctly numbered sequences of sheets, one of thirteen folios numbered 1–13 and a second of eleven numbered 1–11. Each set of sheets corresponds, more or less, to one of the two discrete blocks of text in the Buffalo copybook and there are a further three sheets (unnumbered) between the foliated sequences. The three have no antecedent in the Buffalo copybook. Accordingly, the draft has been identified as a composite document comprising the fruits of two distinct drafting periods, with the unnumbered sheets in-between “drafted later (and possibly individually) as a bridging sequence between the two” (Slote 17). The keystone to this bridging is the transformation scene.

The end of the first section of the Quinn draft features Bloom at Bella’s feet “shamming dead, but with trembling eyelids” (now U 15.2853-54). The second block picks up from “A nymph with hair unbound” descending from her grotto (now U 15.3233ff.). Meeting in the middle of the draft involved producing the first version of what became, in the Gabler edition of “Circe,” almost four hundred lines of intervening text. Linking the two sections resulted in the first primitive version of Bloom and Bella’s sexual transformations—corresponding to about sixty of the four hundred lines—a draft in which Bella is “Bello” throughout and Bloom an unconvincing “Leopoldina” (of three instances of the latter Joyce crossed out two). Yet the scene as it appears in the Quinn draft, however inchoate, fulfils the same role for Joyce as does its panto equivalent: materially it provides a bridge between the two “acts” of the composite document.

The pattern of copybook usage followed by loose-leaf drafting is attested to in the extant dossiers of several episodes of Ulysses, leading Hans Walter Gabler to suggest, “The loose-leaf arrangement seems expressly designed to facilitate a sectional revision in the later phases of the draft composition” (1881). The integration of three sheets into the later “Circe” draft supports this hypothesis and suggests, furthermore, that Joyce used the loose-leaf arrangement to allow for the interpolation of material transitions—of transformation scenes—to bridge previously drafted, discrete sections of episodes.

In the remainder of this paper I examine what the music hall would have meant to Joyce and his contemporaries. By their very nature many of the topical references of Ulysses are lost to a latter-day audience; to one of “Circe’s” earliest readers, T. S. Eliot, however, the music hall element was so clearly figured in Joyce’s typescript that he composed a new beginning to The Waste Land in response, which included a vaudeville scene (Annotated “Waste Land” 18-19). The Internet is a powerful tool for bridging this gap of ages—we can become aware of the popular culture milieu that Ulysses draws on if we cannot achieve Eliot’s level of familiarity with it (XIX). The penchant of the “gentleman lodger,” for example, for “pictures cut out of papers of those skirtdancers(17) and highkickers” (U 13.702-4) that both fascinates and repels Gerty MacDowell can be illustrated if not explained by recourse to period photographs and postcards. But how does one read the end of “Sirens” or the extended execution scene of “Cyclops” when one knows that Pat Feeney (1850-1889), “after Ashcroft the most finished Irish Song-Comic of all” (Watters 97), often appeared on stage dressed as Robert Emmet? Or does it matter that in “Circe” Mrs. Cunningham, as she capers anew with an umbrella, sports an anachronistic merry widow hat(18) (U 15.3857)? This article of millinery was first designed for the 1907 The Merry Widow—the English adaptation of Franz Lehár’s operetta Die lustige Witwe. So widespread was the fashion for the hat that it quickly fed back into the culture from which it had come, however. Clare Kummer penned an 1908 song, “When Mary wears her Merry Widow Hat,” and Helen Sherman Griffith’s one-act farce “The Merry Widow Hat” was published the following year. Mrs. Cunningham, therefore, wears on her head an oversized crinoline hat as suffused with textuality as Stephen’s wide Hamlet hat, one whose meaning is refracted back and forth from stage to street to sheet music, from theatrical costume to high fashion to music hall.

In the portion of the Paris-Pola notebook compiled in 1904, we find the aphorism—apparently original to Joyce—“The music hall, not Poetry, a criticism of life.” Even in the provincial Dublin halls, audiences could expect to see everything from performing lions and boxing kangaroos—alas, not pitted one against the other—to champion swimmers going through the motions in tanks of water on stage. Despite their air of misrule, however, the music halls were a deeply conservative force. (Joyce’s contemporary and, indeed, our modern British tabloids are a useful analogue to bear in mind.) Lions would make great play of mocking political figures and singing their downfalls but this was licensed burlesque rather than any kind of class radicalism. When the Shah of Persia paid a state visit to England in July 1888, for example, the lion comique Pat Kinsella appeared at Dan Lowrey’s as “His Ever-Serene & Sublime Highness the Shah of Dublin, King Patroshki Kinsella.” With war threatening, “Admiral Pat Kinsella” would enact the Defence of Dublin. When a rival Tom Costello sang “Died like a True Irish Soldier,” he was followed by “General Kinsella” singing “Died like a True Irish Tailor” (XX).

The mixture of high and low culture on and off the music hall stage existed, for the most part, in a definite hierarchy with high being invoked to lend an air of respectability to the proceedings. Programmes for the various halls inscribe the list of turns in a space surrounded entirely by advertising. See this programme(19) for the London Tivoli in the weeks leading up to Bloomsday. The cover(20) of the same programme portrays a Victorian vision of Arcadia (see also the cover(21) of this programme for the Alhambra). Not too far removed from Ulysses with its dressing-up of Edwardian Dublin in classical mythology. On the other hand, if the pubs in 1904 Dublin had their curates (mixing the Mass with the public house), and Joyce gave the Ormond Hotel its sirens, the music halls went in for a classical allusion, calling their barmaids “hebes” (Watters 23) after the goddess of youth and spring, the cup-bearer of Olympus.

Neither Arthur Symons nor Shaw would have been considered—or have considered themselves—as high culture patrons of a low culture form. In a similar vein, when the impressionist Walter Sickert exhibited a painting of Katie Lawrence, Gatti’s Hungerford Palace of Varieties, Second Turn of Miss Katie Lawrence, at the New English Art Club in April 1888 it was greeted with public and critical outrage (Baron 164-65). The music hall was not a fit subject for art, it seems.

By using Lawrence and the music hall in the crafting of his brothel scene, Joyce lent a theatricality both grimy and flimsy to “Circe,” invoking the many connexions between the halls and the oldest profession that a contemporary audience would have drawn. Some of these are self-evident—the music halls were notorious as the haunts of prostitutes serving the needs of a clientele attracted by what Sir Compton Mackenzie recalled as “peripatetic harlotry” (8); the artistes themselves were often thought of as little more than working girls; both brothels and music halls were targeted by reforming bodies, such as the Social Purity Alliance, which saw the halls as places that encouraged the consumption of alcohol, smoking and other vices of the working class (O’Connor 16); and both bodies had loyalties to the soldiery. During the First World War, various artistes even ran recruitment drives.

But as much as the music hall was associated with the brothel, the brothel mimicked the mores of the music hall. Austin Briggs reports that turn-of-the-century prostitutes often took their “stage names” from the theatre (52)—by using Lawrence’s name, Joyce riffs on what may have been an established bordello practise. Though he emphatically removed the name (XXI), the concomitant network of associations with the music hall remains. In the published editions of “Circe,” the introduction of Kitty Ricketts describes her as “a bony pallid whore in navy costume” (U 15.2050: emphasis added)—a detail that recalls Katie Lawrence’s getup on the cover of the sheet music for both “The Ship that Belongs to a Lady”(22) and “Oh! Jack, You Are a Handy Man.”

Despite her superstar status in the 1890s, Lawrence died in 1913 pretty much penniless. This notwithstanding, one might argue that even by 1920 surely Katie Lawrence would have been too well known to use as the name of a prostitute. The fact that Joyce first uses the less familiar form of her name and then removes it so early in the drafting of “Circe” may suggest that it was only a temporary measure. On the other hand, we do have the name Henry Flower in the final text of Ulysses—a name that to a 1904 Dublin audience (the fictional Martha Clifford included) cannot but have recalled Constable Henry Flower, the D. M. P.-man accused of Bridget Gannon’s murder in August 1900.

While the all singing, all dancing music-hall correspondences of Ulysses are not as far-reaching as the Homeric ones, their presence—and the manner of their partial elision—have important implications for the more obvious intertexts of the book. In dismissing the Homeric correspondences of the novelin his “Paris Letter” of June 1922, Ezra Pound famously argued that the correspondences were “part of Joyce’s mediaevalism and […] chiefly his own affair, a scaffold, a means of construction, justified by the result, and justifiable by it only” (XXII). This is in marked contrast with the position adopted by T. S. Eliot in “Ulysses, Order and Myth,” published the following year. Eliot saw Joyce’s “continuous parallel between contemporaneity and antiquity” as “simply a way of controlling, of ordering, of giving a shape and a significance to the immense panorama of futility and anarchy which is contemporary history” (XXIII). The presence of someone like Lawrence in Ulysses offers a halfway house between these two interpretations. Correspondences have a clear compositional purpose—as Pound maintained—but their presence in Ulysses is not a traceless one. And I’ll finish with a graphic illustration of what I mean by this.

painting(23)

Walter Sickert produced some hundred and sixty-six preparatory sketches of Katie Lawrence performing at Gatti’s Hungerford Place of Varieties in 1887 (Baron 165-66). They formed the basis of a number of paintings he made of her in the 1880s and around 1903. Only one painting, that from around 1903, survives; the rest are presumed destroyed. In 2005, however, while this painting was undergoing routine restoration work, it was discovered that the Katie Lawrence scene was actually painted over an earlier composition. Using X-rays, art restorers discerned a study of the exterior of a church (of all things)—the façade of St Jacques in Dieppe—beneath the music hall scene ( ). And to my mind this encapsulates the role of the correspondences in Ulysses. A “means of construction,” yes, but one which we can discern and enjoy within the published text.

Works cited.

Baron, Wendy. Sickert: Paintings and Drawings. New Haven, Conn.; London: Yale University Press, 2006.

Briggs, Austin. “Whorehouse/Playhouse: The Brothel as Theater in the ‘Circe’ Chapter of Ulysses.” Journal of Modern Literature 26.1 (Fall 2002): 42-57.

Carter, Alexandra. Dance and Dancers in the Victorian and Edwardian Music Hall Ballet. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2005.

Dredge, Paula and Richard Beresford. “Walter Sickert at Gatti’s: New Technical Evidence.” The Burlington Magazine 148 (April 2006): 264-69.

Eliot, T. S. Selected Prose of T. S. Eliot. Ed. Frank Kermode. London: Faber, 1975.

––––––––. The Annotated “Waste Land” with Eliot’s Contemporary Prose. Ed. Lawrence Rainey. 2nd Edition. New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2005.

Ellmann, Richard. James Joyce. New and rev. ed. Oxford, London and New York: Oxford University Press, 1982.

Herr, Cheryl. Joyce’s Anatomy of Culture. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986.

Jackson, Holbrook. The Eighteen Nineties. London: Grant Richards Ltd, 1913.

Jastrebski, Joan. “Pig Dialectics: Women’s Bodies as Performed Dialectical Images in the ‘Circe’ Episode of Ulysses.” James Joyce and the Fabrication of an Irish Identity. Ed. Gillespie, Michael Patrick. Amsterdam and Atlanta: Rodopi, 2001. 151-75.

Joyce, James. The Workshop of Daedalus: James Joyce and the Raw Materials For “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.” Eds. Robert Scholes and Richard M. Kain. Evanston, Ill.: Nortwestern University Press, 1965.

––––––––––. Ulysses: A Facsimile of the Manuscript. Eds. Harry Levin and Clive Driver. 3 vols. London: Faber and Faber Ltd. in association with the Philip H. & A. S. W. Rosenbach Foundation, 1974.

––––––––––. Joyce’s Notes and Early Drafts For “Ulysses”: Selections from the Buffalo Collection. Ed. Phillip F. Herring. Charlottesville: Published for the Bibliographical Society of the University of Virginia by the University of Virginia, 1977.

––––––––––. Ulysses: A Critical and Synoptic Edition. Eds. Hans Walter Gabler, et al. 3 vols. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1984.

Kift, Dagmar. The Victorian Music Hall: Culture, Class and Conflict. Trans.Roy Kift. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

McCourt, John. “Joyce’s Trieste: Città Musicalissima.” Bronze by Gold: The Music of Joyce. Ed. Sebastian D. G. Knowles. New York; London: Garland Pub, 1999. 33-55.

Mackenzie, Comtpon. Figure of Eight. London: Cassell, 1936.

Mullhall, Michael G. The Dictionary of Statistics. Part 2. Q – Z. 4th ed, revised to 1898. London: George Routledge & Sons, 1903.

O’Connor, Patrick. “Every Variety of Temptation.” The Times Literary Supplement. August 5, 2005: 16.

Paradise, Paul R. Trademark Counterfeiting, Product Piracy, and the Billion Dollar Threat to the U. S. Economy. Westport, Conn.; London: Quorum, 1999.

Pound, Ezra. Pound/Joyce: The Letters of Ezra Pound to James Joyce, with Pound's Essays on Joyce. Ed. Forrest Read. New York: New Directions, 1967.

Shaw, Bernard. Music in London, 1890–94: Criticisms Contributed Week by Week to “The World.” Vol. 3. London: Constable, 1931.

Slote, Sam. “Preliminary Comments on Two Newly Discovered Ulysses Manuscripts.” JJQ 39.1 (Fall 2001): 17-28.

Spielberg, Peter. James Joyce’s Manuscripts & Letters at the University of Buffalo: A Catalogue. Buffalo: University of Buffalo, 1962.

Symons, Arthur. Selected Letters, 1880–1935. Eds. Karl Beckson and John M. Munro. London: Macmillan Press, 1989.

Watters, Eugene and Matthew Murtagh. Infinite Variety: Dan Lowrey’s Music Hall, 1879–97. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan, 1975.

Wosk, Julie. Women and the Machine: Representations from the Spinning Wheel to the Electronic Age. Baltimore, Md; London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001.

Caption reads:

Arthur Lloyd’s “I Vowed that I Never Would Leave Her.” London: H. D. Alcorn, 1873. This source was identified by Aida Yared. Image courtesy of Peter Charlton and arthurlloyd.co.uk.

Links to: http://www.arthurlloyd.

co.uk/

index.html.

150m.com/Archive

ImagesC/

LottieCollins002.JPG

Caption reads:

A half-tone portrait of Lottie Collins, issued in the mid 1890s with Phillips's Guinea Gold Cigarettes. Courtesy of John Culme’s Footlight Notes Archive.

Link to: http://www.gabrielleray.

150m.com/

ArchiveTextC/

LottieCollins

.html.

uk/images/objects/

cropped2/700/

sch200211130

786-005.jpg

Caption reads:

A souvenir ink well of Dan Leno, created around 1901. Courtesy of the V&A Theatre Collections.

Link to: http://www.peopleplayuk.org.

uk/collections

/object.php?

object_id=792&

back=%2Fguided_

tours%2Fmusic_hall_tour

%2Fmusic_hall_stars

%2Fleno.php%3F.

uk/mediastore/014/005/

014EVA00000000

0U00559000[SVC2].JPG

Caption:

Courtesy of the British Library and Collect Britain. Evanion Collection of Ephemera.

Link to: http://www.collectbritain.co.

uk/personalis

ation/object.

cfm?uid=014EVA0000000

00U00559000&

largeimage=1#

largeimage.

uk/mediastore/

014/005/

014EVA000000000U00

576000%5BSVC2%5D.JPG

Caption:

Courtesy of the British Library and Collect Britain. Evanion Collection of Ephemera.

Link to” http://www.collectbritain.co.

uk/personalisation/

object.cfm?uid=014

EVA0000

00000U00576000&

largeimage=1

#largeimage.

uk/mediastore/

014/007/

014EVA00000000

0U00799000

%5BSVC2%5D.JPG

Caption:

Courtesy of the British Library and Collect Britain. Evanion Collection of Ephemera.

Link to: http://www.collectbritain.co.

uk/personalisation/

object.cfm?

uid=014EVA000000

000U00799000&

largeimage=1#largeimage.

http://webapp1.dlib.indiana.

edu/collections/lilly/

devincent/

216/216014/

LL-SDV-

216014-01-01-

screen.jpg

Caption reads:

Mabon, F. J. and Wm. H. Fry. “Farewell, Daisy Bell.” Shelton, Conn.: Huntington Piano Co., 1905. Courtesy of the Indiana University Sheet Music Collections.

Link to: http://webapp1.dlib.indiana.

edu/sheetmusic/devincent

.do?&

id=LL-SDV-216014&

q1=LL-SDV-216014&

sid=69d2c55f61df3

b2ca78da9a

31455a7e2.

uk/images/obje

cts/cropped2/

300/sch2002070104

90-001.jpg

Caption reads:

Lottie Collins on the cover of Richard Morton and Angelo A. Asher’s “Ta-ra-ra-boom-de-ay.” London: Charles Sheard & Co., 1895. Courtesy of the V&A Theatre Collections.

Link to: http://www.peopleplayuk.org.

uk/collections/obj

ect.php?object_id=386&

back=%2Fcollections%2Fdefault.

php%3Fsearch_name%3Dperformance_

category_search

%26amp%3Brun_

search%3Dtrue%26amp%3Bc

performance_

type%3DMusic%

2Bhall%2Band%2B

variety%26amp%

3Bctab%3D3&

search_result=true.

uk/images/obj

ects/cropped2/

300/sch200212

160967-006.jpg

Caption reads:

Harrington, J. P. and Geo Le Brunn. “Salute My Bicycle.” London: Francis, Day & Hunter, 1895. Courtesy of the V&A Theatre Collections.

Link to: http://www.peopleplayuk.org.

uk/collections/

object.php?

object_id=565&back=%2F

collections%2Fdefault.php

%3Fsearch_name%

3Dperformance

_category_search

%26amp%3

Brun_search%3Dtrue%26amp%3

Bcperformance_type%3D

Music%2Bhall%2Band

%2Bvariety

%26amp%3Bctab%3D

3&search_result

=true.

uk/images/obje

cts/cropped2/

300/sch200210

250734-012.jpg

Caption reads:

A trick cyclist balances his machine on two candles. Courtesy of the V&A Theatre Collections.

Link to: http://www.peopleplayuk.org.

uk/collections/object.

php?object_id

=289&back

=%2Fcollections%2

Fdefault.php

%3Fsearch_name%

3Dmuseum_search%

26amp%3Bfree_text%3Dbicycle

%26amp%3Brun_search.x

%3D0%26amp%3Brun_search

.y%3D0&search_

result=true.

uk/images/obj

ects/cropped2/

300/sch200203

010391-002.jpg

Caption reads:

George Leybourne as a swell on the cover of Alfred Lee’s “Champagne Charlie.” London: C. Sheard, 1867. Courtesy of the V&A Theatre Collections.

Link to: http://www.peopleplayuk.org.

uk/guided_tours/

music_hall_tour/

music_hall_stars/

leybourne.php.

uk/images/objects/

cropped2/

300/sch20021202

0886-004.jpg

Caption reads:

Vesta Tilley as a male impersonator on the cover of E. W. Roger’s “The Latest Chap on Earth.” London: Francis, Day & Hunter, 1899. Courtesy of the V&A Theatre Collections.

Link to:

http://www.peopleplayuk.org.

uk/guided_tours/

music_hall_tour/

music_hall_

stars/tilley.php.

uk/mediastore/

014/025/

014EVA000000000U02

562000%5BSVC2%5D.JPG

Caption:

Courtesy of the British Library and Collect Britain. Evanion Collection of Ephemera.

Link to: http://www.collectbritain.co.

uk/personalisation/

object.cfm?

uid=014EVA00000000

0U02562000&

largeimage=1#largeimage.

uk/images/obje

cts/cropped2/

300/sch200210030640-002.jpg

Caption:

Letty Lind’s skirt dance. Courtesy of the V&A Theatre Collections.

Link to: http://www.peopleplayuk.org.

uk/collections/

object.php?

object_id=34&back=%2Fguided_tours

%2Fdance_tour

%2Fpopular_theatre

%2Fmusic_hall

_skirt.php%3F.

uk/images/

obje

cts/cropped2/

700/sch20030

3311230-005.jpg

Caption:

Lily Elsie with merry widow hat. Courtesy of the V&A Theatre Collections.

Link to: http://www.peopleplayuk.org.

uk/collections/

object.php?

object_id=1397&search_

result=true&back=%2F

collections

%2Fdefault.php

%3Fsearch_name%3D

performance_cate

gory_search

%26amp%3Brun_search%

3Dtrue%26amp%3B

cperformance

_type%3DMusic%2Bhall

%2Band%2Bvariety%26

amp%3Bctab%3D3.

uk/images/objec

ts/cropped2/

300/sch2002120208

82-003.jpg

Caption:

Programme for the London Tivoli, 1904. Courtesy of the V&A Theatre Collections.

Link to: http://www.peopleplayuk.org.

uk/collections/object

.php?object_id=788&back=%2

Fcollections%2Fdefault

.php%3Fsearch_name%3D

performance_cate

gory_search

%26amp%3Brun_search%3

Dtrue%26amp%

3Bcperformance

_type%3DMusic%2

Bhall%2Band%2Bvariety

%26amp%3Bctab%3D3&

search_result=true.

uk/images/obje

cts/cropped2/

300/sch200212

020882-004.jpg

Caption:

Programme for the London Tivoli, 1904 (cover). Courtesy of the V&A Theatre Collections.

Link to: http://www.peopleplayuk.org.

uk/collections/

object.php?object_

id=788&back=%2F

collections%2F

default.php%3F

search_name%3D

performance_cat

egory_search

%26amp%3Brun_search%3Dtrue

%26amp%3Bcperformance

_type%3DMusic%2Bhall%2

Band%2Bvariety%26

amp%3Bctab%3D3&search

_result=true.

uk/images/obj

ects/cropped2/

300/sch2002100

30634-007.jpg

Caption:

Programme for the London Alhambra, 1898 (cover). Courtesy of the V&A Theatre Collections.

Link to: http://www.peopleplayuk.org.

uk/collections/

object.php?search_result

=true&object_id=703&

back=%2Fcollections%2F

default.php%3Fsearch_name

%3Dobject_category_search

%26amp%3Brun_search%3Dtrue

%26amp%3Bcobject_type

%3DProgrammes%26amp

%3Bctab%3D19.

I S. Joyce, Book of Days, 5 July 1907, cited in McCourt 42.

II Up until the first decade of the twentieth century, music halls dancers were generally of Italian stock and training. Carter 32.

III See Facsimile MS “Circe” fol. 83 for Kelleher’s remark. It was shortened on the second setting of Gathering 36 in January 1921 (JJA 26.333-36).

IV Long years ago when men were men and fancied May Oblong

Or lovely Becky Cooper or Maggie’s Mary Wong

One woman put them all to shame, just one was worthy of the name,

And the name of that dame was Dicey Reilly.

V Facsimile MS “Oxen of the Sun” fol. 34.

VI The Era. June 19, 1859: 10; Liverpool Mercury etc. April 20, 1882: 6; Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper. June 24, 1883: 8; “Pupil Teachers’ Religious Examination.” Trewman’s Exeter Flying Post or Plymouth and Cornish Advertiser. February 18, 1893; “Downie Bursary at Laurencekirk.” Aberdeen Weekly Journal. April 18, 1896: 7; “Madwoman on a ’Bus.” Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper. January 17, 1897: 1. With the exception of The Irish Times, all newspapers quoted from in this paper were consulted on the database 19th Century British Library Newspapers.

VII The Entr’acte. June 30, 1883: 14b.

VIII Arthur Symons, to the editor of The Star.October 19, 1891: 2. Reprinted in Symons 86. Symons also wrote (under the name “Silhouette”) on Lawrence in his “An Artist in Serio-Comedy: Katie Lawrence.” The Star. March 26, 1892: 4.

IX Shaw wrote on Lawrence, in his capacity of music critic for The World, on January 24, 1894. Reprinted in Shaw 147.

X Freeman’s Journal. February 16, 1885: 4; The Era. February 21, 1885: 18; The Belfast News-Letter. March 11, 1885: 1. Both premises were established by Dan Lowrey. He founded the Belfast Alhambra in the 1870s and, once construction on the Dublin hall was well underway, sold the former in 1879 to W. J. Ashcroftthe same Ashcroft alluded to in the opening of Finnegans Wake: “erse solid man” (FW 3.20). Watters 13-19 (hereafter cited in the text).

XI “Provincial Theatricals.” The Era. September 5, 1885: 16.

XII The Irish Times.September 19, 1904: 4.

XIII The Era.October 11, 1884: 12; The Era. May 15, 1886: 24; “Music Hall Gossip.” The Era. March 25, 1893: 17; The Belfast News-Letter. August 9, 1892: 1; The Era. August 13, 1892: 15.

XIV “Advertisements & Notices.” The Era. January 21, 1888: 24; “Music Hall Gossip.” The Era. October 8, 1892: 17; The Era. August 1, 1896.

XV The same Board of Trade returns for 1891 gave the average income for a woman at 9/4. Mulhall 817.

XVI Much of the pirate material emanated from America, Canada or Australia and it flooded the English market in the late 1800s, leading to the founding of the Music Publishers Association in 1881. The Association estimated that “90 percent of printed sheet music coming into England from American consisted of pirated reprints of English copyrights.” Paradise 15-16.

XVII “Preliminaries.” The Belfast News–Letter. September 4, 1893: 5; The Irish Times. June 19, 1895: 4; The Irish Times. December 8, 1897: 4.

XVIII “Miss Kate Lawrence, the serio-comic vocalist, who is well known to music hall goers, is taking splendidly.” The Belfast News-Letter. June 5, 1895: 5.

XIX Aida Yared’s “Joyce Images” [ http://www.joyceimages.com/ ] gathers together a wealth of such material.

XX Workshop 88. Turn five on the programme of the Star Theatre of Varieties (another incarnation of Dan Lowrey’s) for the week ending January 7, 1893 was listed as “the boxing kangaroo.” The performing lions took to the stage in 1884. Watters 68, 108, 115.

XXI In the transfer of the first block of Buffalo copybook text into the next document in the sequence of textual development, a copybook that is now at the National Library of Ireland, Joyce twice neglected to incorporate his changes to Kitty’s name. “Kitty Lawrence” appears in stage directions on pages 12r and 16r (both subsequently revised). The name “Kate Ricketts” appears twice in the basic text on page 19r (and it is not revised there) but the facing verso contains an addition with the final form of the name, “Kitty Ricketts.”

XXII From Pound’s “Paris Letter.” The Dial 72.6 (June 1922): 623-29. Reprinted in Pound 197.

XXIII From Eliot’s “Ulysses, Order, and Myth.” The Dial 75.5 (November 1923): 480-83. Reprinted in Selected Prose 177.

XXIV Dredge 264-65. An X-radiograph of the painting, rotated 90° clockwise and showing the Dieppe scene, is also reproduced (266).